Visiting Grosse Ile took some tenacity. We had to set an alarm clock, which we haven’t done in months. Then, when the alarm went off, the weather was terrible — cold and rainy. Still, this was our one opportunity to visit and I had read good things about the site. As Doug says, Who can resist costumed interpreters? The drive from Quebec to Berthier sur Mer took longer than anticipated and we arrived at the dock in the nick of time, without having had any breakfast. But we were able to board, and even buy two sack lunches to bring along. A relief.

The positive side of visiting on a rainy day was the small numbers. There were 45 of us on the ferry, and the guide said typically there were 100, but the ferry can hold 200 and often does.

The ferry ride took about 45 minutes, and the captain made a lot of remarks that were very funny. At least I assume so, because everyone laughed heartily. Unfortunately, we don’t speak French.

But don’t get the impression that we were treated poorly — everyone went out of their way to interpret the important things. When we arrived on the island, our group of 45 was divided into smaller tour groups by language. The English-speaking group consisted of 8 people, including a couple from Toronto, Richard and Gloria, who were retired schoolteachers, and four friends who came well-prepared since some of them had done the tour before.

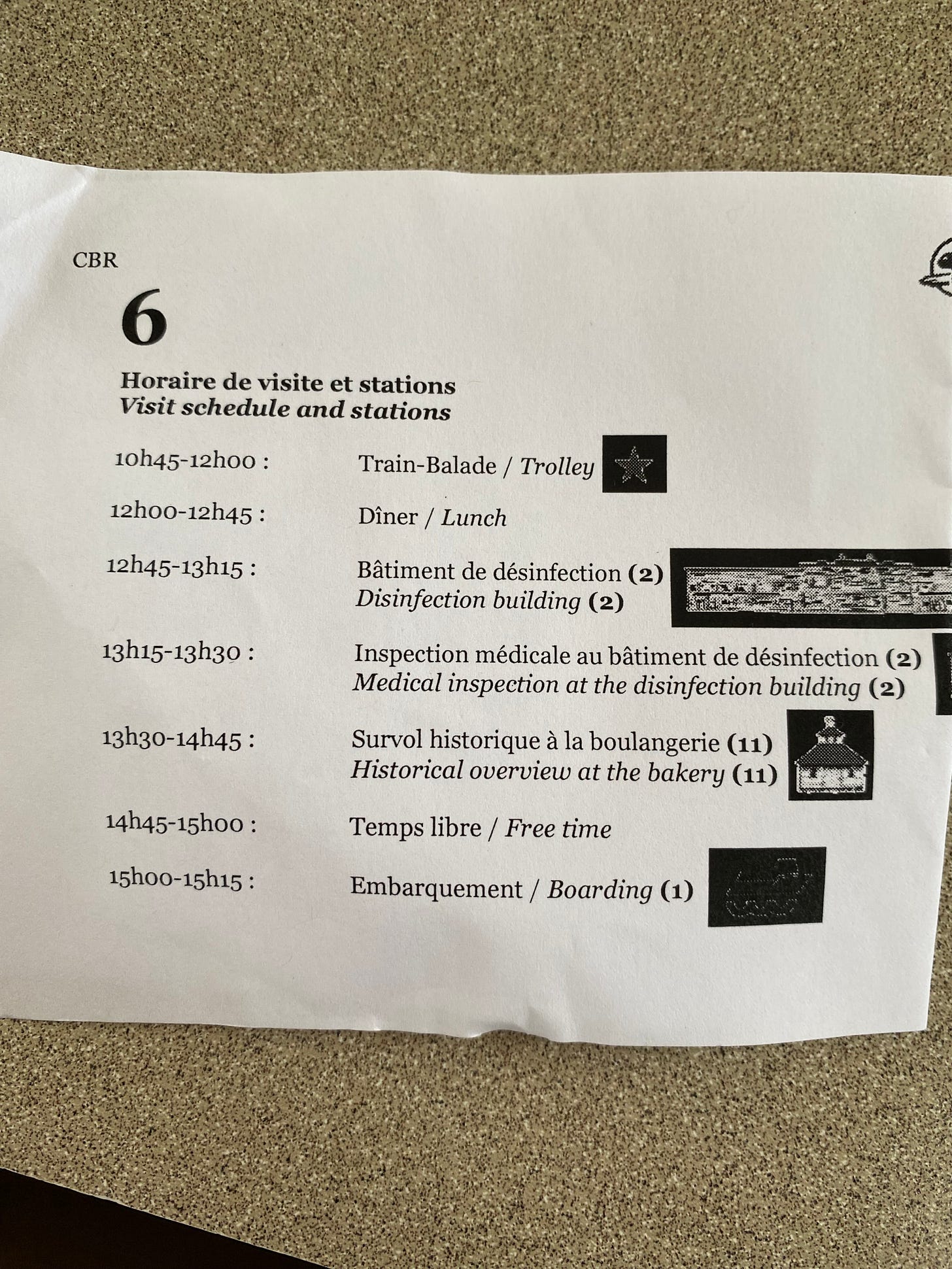

We were handed a fairly detailed and complex schedule of how we would spend our five hours on the island, including a walking tour, trolley ride, and tours through various buildings where we encountered first-person interpreters. A 45 minute lunch period was built in, and we could eat our sack lunches in the second-class dormitory.

(My only unmet need was for a cup of coffee. But spending a day thinking about plagues does help with perspective.)

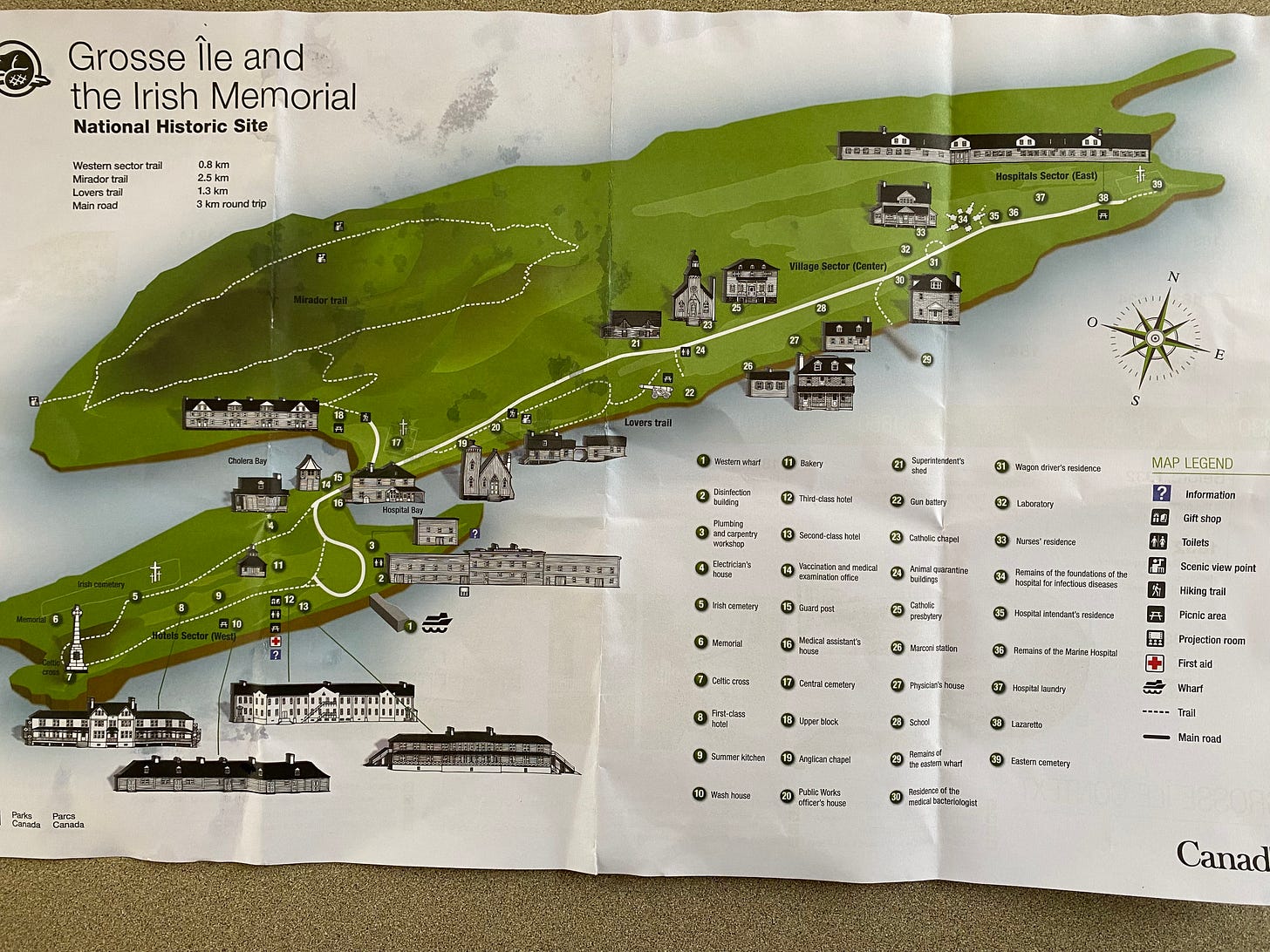

The island has a 105-year history as a fumigation (or disinfection) immigration station and interprets 3 main events:

Immigration during the 19th and 20th centuries in general.

A fumigation station, as there are very few left.

The so-called Irish tragedy of 1847 which involves the typhus fever.

It was raining when we got off the ferry, and after a brief introduction, our small group boarded a trolley. As we drove, our guide gave us some back story.

In the 1800s Canada welcomed immigrants because they needed people to fill their vast reaches. In the early days they didn’t understand how disease spread. This is called the “Improvisation Period” (1832-1880) because, as diseases occurred, they improvised solutions. The prevailing theory was of Miasma — that disease came in the air and the defense against it was perfume and religion. Hence they sent in priests. Then Microbes were discovered in 1880. This began the “Modernization period.”

Four main diseases swept through the island in repeated waves: cholera, typhus, smallpox and dysentery. The need for medical care was met by putting up hospital-type facilities that were prefabricated in Quebec. They were called Lazarettos, and we toured the one remaining building. Each Lazaretto was designed to hold 300 patients, but at times needed to hold four times that many. I believe there were eight Lazarettos in total. Just to give a sense of the need and human tragedy that unfolded here.

Along our trolley ride we saw:

a Catholic chapel which was interpreted by a woman impersonating the daughter of the superintendent, who was in charge of all things on the island.

an original ambulance which was purchased just 20 years after invention, very cutting-edge

a sidewalk which the Abbott ordered to be installed to keep his skirts clean. (Once again the idiocy of religious professionals on display.)

a Marconi station — these are sprinkled throughout Canada

three cannons from when the military ran the island, to encourage ship captains to stop. Stopping disease became a high-stakes game.

Back in the main medical facility, another First-Person interpreter gave us the same medical inspection which passengers experienced. The nurse wore a white outfit and clicked her heels as she strode up and down the line, speaking very sternly. She had us perform a 3 point inspection:

Pinch fingernails and release to check circulation — does the white turn pink?

Check lymph nodes for swelling.

Check tongue for white or black.

We toured the chambers where baggage was disinfected, and the “showers” where passengers were doused with mercury bichloride. So sobering.

Then we walked to the Irish cemetery, where 47 crosses cover the hills, a remembrance of 1847, when more than 5,000 people were buried here. (Not counting all those buried at sea.) There’s been an attempt to record the names of all the deceased, but some are unknown because people afflicted with typhus literally lose their tongues.

How poignant to think of being unable to communicate your name, and your existence being lost to history.

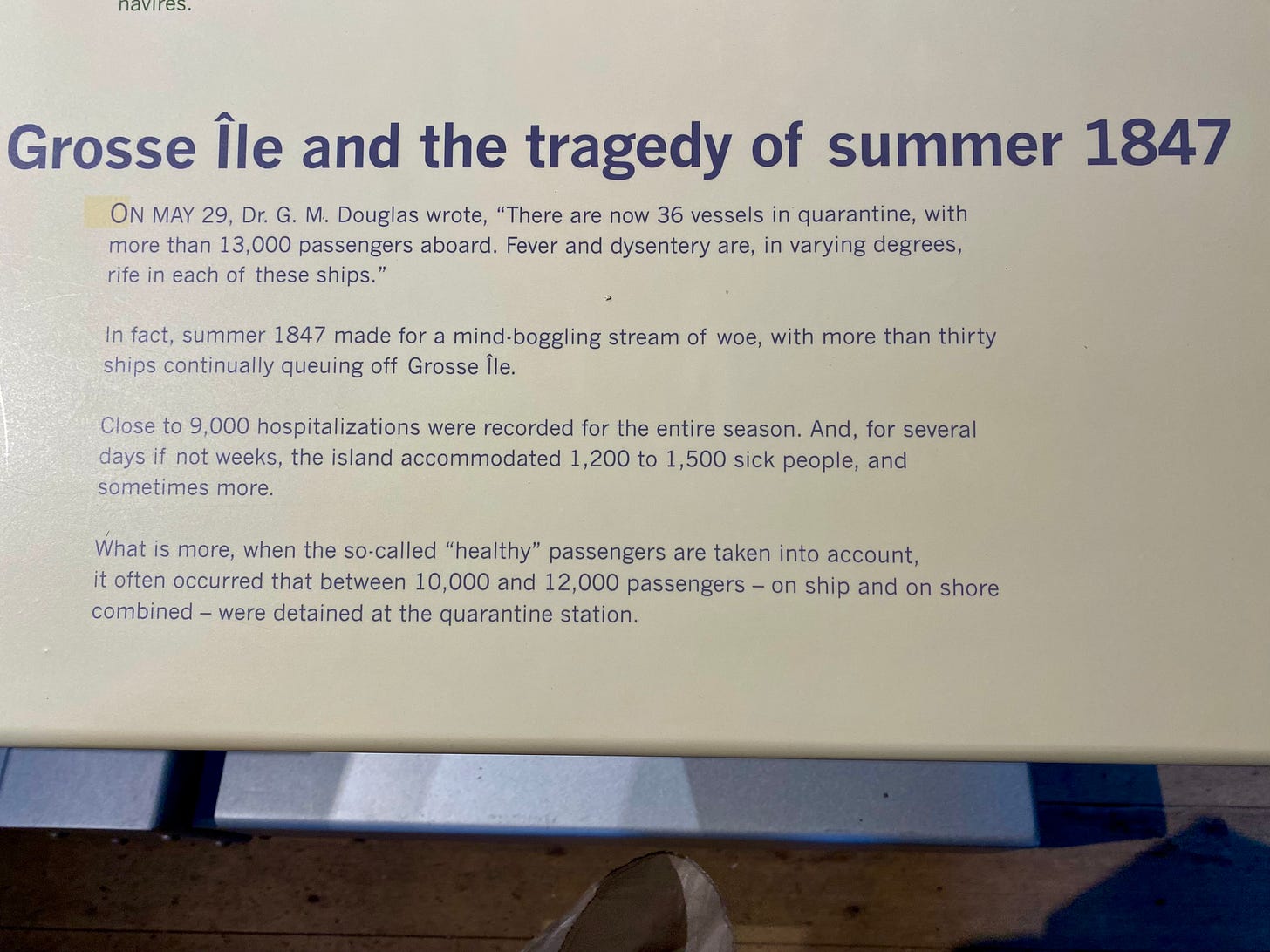

The guide told us about Typhus Ships, or coffin ships, which could be smelled before they arrived. So many of those arriving were Irish who were fleeing the potato blight. The combination of potato blight and typhus is referred to as the Irish tragedy. Ireland has never recovered its population numbers since.

A long, interesting day, and well worth the cost, time, and trouble to experience it.

That is absolutely mind boggling. I can't imagine how awful conditions must have been for everyone associated with this.